|

|

For many years, the big hole in my education has been the structure and theory of music. I love music and have listened to many types of music—classical, rock, country, Celtic, and new age or electronic—all my life. Certain passages and even some basic chord progressions can bring tears to my eyes. But if I thought about it, I did not know why. And that bothered me.

Like most children in suburban public schools in the 1950s and ’60s, I was invited to play an instrument in the fourth grade. This was partly for music appreciation and partly a recruitment process for future junior-high and high-school bands in the district. My instrument was the trombone, and I played it badly. Although I took regular lessons, was given the étude books to work on, could read music—more or less—in the bass clef, and was theoretically committed to practicing on the instrument for an hour a day, I was still bad at it. Partly, this was because I was bored with the exercises and cheated on the practicing. Partly because, with all that training, I still didn’t know what I was doing.

For one thing, I was hazy on those sharps and flats shown on the staff at the beginning of each composition. I tended to forget that the sharp or flat way up there governed every other note on that line or space throughout the piece, unless there was a sharp, flat, or natural sign attached to single notes to counter it. I knew those leading sharps and flats had something to do with the “key signature,” but since I had no working knowledge of what a “key” actually was—other than that plonky, push-down thing on the keyboard—it didn’t mean much to me and so I tended to ignore it.

For another thing, I had no concept of chords and harmony. The trombone, like all brass instruments, is a one-note instrument: toot, toot, and toot. What you blow is what you get. If the composer wants a chord from the brasses or woodwinds, he or she assigns different parts to the different “chairs” in the section, one to play the root note and the others to chime in with the harmonics. But as a single player sitting there, all you know is you’re playing a different note from the fellow beside you.

At the same time, at home my dad was learning to play the organ—his school instrument had been the violin—and so we had a Hammond B-3 in the living room. I would dust it as part of my weekly chores, and that got me fooling around with the drawbars to make different sounds. I even learned to play one simple two-handed song, although I had no idea what the left hand was actually doing when I held down those three keys at once, but it sounded nice. So three years ago, when I decided to correct that hole in my education, I bought myself an organ—a Hammond XK-3c, because I already had a feel for how the drawbars put together each note from the different pipe-organ lengths, and also for old time’s sake—and began taking keyboard lessons. I also bought a set of lessons on music fundamentals from The Great Courses and worked my way through them.

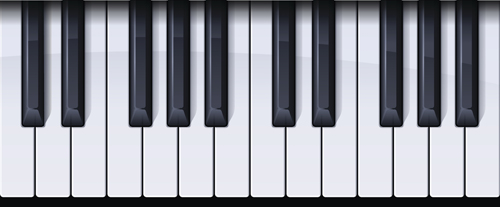

What I’ve learned since then is a revelation as to the structure of music. Start with the keyboard, which is standard for all pianos, organs, synthesizers, harpsichords, accordions, and anything else that plays polyphonic—that is, “many voiced”—music by pressing down keys with your fingertips. Those keys represent a repeating pattern of twelve notes, seven in the white keys and five in the black. Even my childhood music training had taught me that the white keys were whole tones and the black keys half-tones: sharps a half a step up from the previous key, and flats half a step down from the next key. But why they were arranged in that pattern of two blacks together followed by three blacks was a mystery. If these were the whole and half steps, then shouldn’t there be a black key between each white key, evenly spaced out, like inch and half-inch marks on a ruler? And why were two of the white keys stuck together in that series?

No one had ever told me before about the musical modes. What we hear when we sing do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do in school is not a simple whole-note progression. It sounds like that to our ears, because we’re familiar with it. But actually, what we’re singing and hearing is a varied pattern: whole step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole, whole, whole, half step.1 If you play that out on just the white keys of the piano starting at C (the white key immediately to the left of the first group of the two black keys) and ending at C an octave higher, you get the C-major scale.2 This pattern of wholes and halves is called the “Ionian mode.”

The modes go back to the ancient Greeks and their music, and so the names have Greek references. They were actually refined and organized in the Europe of the Middle Ages. There are six other modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. You can hear each of these modes by playing the scale on only the white keys starting with the next higher note above C (that is, D, E, F, G, A, and B).3 The patterns represented by the other six modes just sound wrong compared to the C-major scale we’re all familiar with.

|

So then, what are the “key signatures”? Simply put, they are ways to move that eight-note Ionian pattern up and down the keyboard—a process called transposing—to accommodate the limited range of most people’s singing voices. You can recreate that T-T-T-s-T-T-T-s by starting with D instead of C but only if you sharp the F and C—or, conversely, flat the G and D—and that’s the key of D major.4 Or you can start in E and sharp the F, C, G, and D. You just work your way up the keyboard, sharping or flatting notes to recreate that whole-and-half-step pattern of the Ionian mode. So, to correct my earliest misunderstanding, the sharps and flats shown at the start of a composition, the key signature, are not just random, arbitrary adjustments to the notes. Instead, the key signature transposes the familiar scale up or down the keyboard to make it easier for people to play and sing.5

Finally, I’ve learned the other mystery of my early education, chords and harmony. The basic pattern is the triad, starting with the root note and adding the third and the fifth. So, with the root in C, the third is E, and the fifth is G. That makes a pleasing sound and one richer than just the root note by itself. With the root in D, the third is F sharp and the fifth is A. And so on. But as with everything, there are complications. If you flat the third (Eb in C), you get a minor chord. If you add in the whole note just below the root, you get the seventh chord. Add the whole note above the root but an octave higher, and you get a ninth. And so on and on. All of this makes the set of sometimes pleasing, sometimes jarring sounds that so move us in music.6

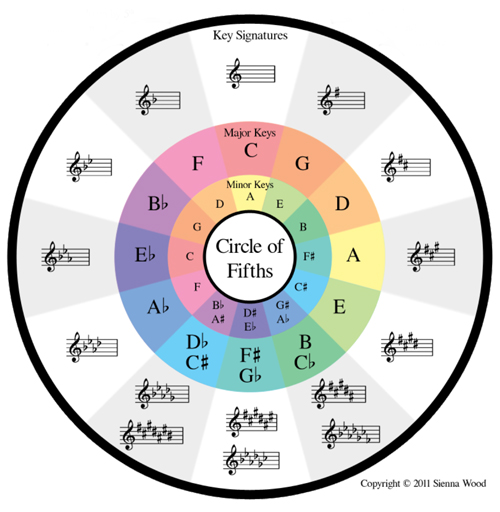

The organization of the key signatures is best described by the “Circle of Fifths,” as shown nearby. Each key signature derives from the fifth note of the key that came before. So the key of C major, with no sharps or flats, yields the scale based on its fifth, G, with one sharp (F#, or, conversely, Gb), which yields the scale based on its fifth, D, with two sharps (F# and C#, or Gb and Db), which yields its fifth, A, with three sharps, and so on around the circle until you come back to C major.

The whole thing works because these various vibrations sound in the human ear—at least, one that has been culturally attuned to hear them—as pleasing patterns. It all makes sense in a mathematical and physical way. And that’s what I came to learn.

Now I just have to put in the practice to embed this knowledge in my nervous system and have it come out my fingertips. But luckily, my teacher has me working from actual songs and progressions of chords built into them, rather than the dry and mechanical études I studied with the trombone and found so boring. So teaching has come a long way since my childhood, too.

1. For simplicity in notation, music theorists use tone (T) to represent a whole tone or step and semitone (s) for a half tone. So the pattern is conventionally written as T-T-T-s-T-T-T-s.

2. Actually, each key—black or white—on a piano or organ keyboard is just a half tone above the previous key. The spacing within and around the two groups of black keys clearly shows this, with the white keys playing the whole tones and the intervening black keys playing the half tones. However, the two white keys set side by side between these two groups of black keys—at E and F above the two black keys, and again at B and C above the three black keys—yield the half tones required by the Ionian mode.

3. Why our most familiar mode, the Ionian, starts with C and not with A is a matter of both history and physics. The letter names for the notes came from the work of a late Roman philosopher, Boethius, and the A corresponded with what he considered the lowest note on his scale, then went up through the eight notes to G. He was not, however, working with the various modes as we practice them today, and his lowest note is not today’s A above middle C, also called “A440,” because it sounds a vibration of 440 Hertz.

4. Minor scales are built using the same sharps and flats as the major scale but start on the sixth note of the major. Thus, a minor scale built on C uses the same notes as the C-major scale, but starts with A and so is known as the A-minor scale. That makes an entirely different pattern of whole and half steps. No wonder I was confused as a child in the fourth grade!

5. As part of my keyboard instruction, I’ve also had to learn oddities like the “blues scale,” which represents a seven-note pitch sequence—not eight—that is quite different from the various classical modes. The blues involves minor thirds, and develops a strange pattern: whole tone, minor third, whole, half, half, minor third, whole. So with the blues in F, the scale is F, Ab, Bb, B, C, Eb, F. It’s a strange but beautiful sound.

6. Generally, to my and to most people’s ears, the major chords are bright and happy, while the minors are a bit dissonant and a little depressing. And some chords and their progressions play very well as accompaniment to horror movies.