|

|

Surprise fact: We are all, every one of us, going to die someday. You, personally, may harbor the secret belief that you are that rare exception, the fairy changeling replaced in the cradle soon after birth, who will live on and on, never changing, never growing old, and eventually mourning your friends and family long dead a hundred, a thousand, ten thou—or forever from now. But, as Damon Runyon would say, “That’s not the way to bet.”

We all know that we’re going to die someday. That is the curse of being a human with an intellect capable of self-awareness—the perception of oneself as a separate entity in relation to time, space, and the world around us. Dogs and cats don’t have this awareness, and so they live in the moment, never questioning tomorrow. Dolphins, whales, and elephants may have it, and so they might recognize themselves as separate beings with pasts and futures that can be considered, probed, and defined intellectually and emotionally. This awareness seems to be the dividing line between the intelligence we recognize in other human beings and the degrees of relative awareness and responsiveness we see in other animals. It is, in my opinion, the first step in defining the human condition.

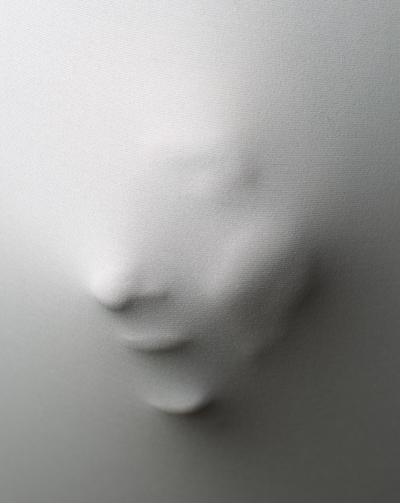

With this self-awareness, we can look at a dead bird on the sidewalk, a blue jay that used to fly by our window in the morning, or see a rotted log in the forest, a tree in which we once carved our initials inside a heart, and think: “This is death. This is a sign of time’s passage. This is what comes at the end of life. One day this will be me.” It is the memento mori, “remember that you are mortal.” It is the foundation of both human joy and grief: joy in the moment of living, and grief with the knowledge of life’s passing.

But in everyday life a veil descends on the human mind. We put away these death thoughts. We let our hopes—or that secret belief in our changeling exception—grow to dominate our thinking about life and the future. And we succumb to the persistent distractions of our work and hobbies, our love and other pleasures, our expectations and plans, and the daily round of whatever we have to do next. This is another Jedi Mind Trick.1

Are we fooling ourselves about death? Yes, probably, in a strict-constructionist sense. Death is inevitable: for you and me personally, when we grow old and our brains or our bodies outlive their usefulness; for this planet eventually, in five billion years or so, when the Sun blows up and blasts away the Earth’s surface; and for the universe itself ultimately, when the expansion of dark energy smears space into a tenuous wisp of dissociated molecules, or the process reverts under the influence of some kind of dark gravity that contracts space back into a tiny, dense spot. Change is inevitable. And part of change is the possibility of ending.

But the fooling—the foolish dream of living on, as if death itself doesn’t matter—is necessary to becoming a fully functioning human being. Otherwise, the first time we learned as a child that things die—the passing of that pet goldfish or hamster or, in my case, a parakeet—we would totally absorb the lesson that life is futile. We would collapse into the fetal position, take only shallow and shuddering breaths, and never rise to hope again.

I’ve mentioned elsewhere2 that one definition of an adult is someone who has come to grips with the knowledge that one day he or she is going to die. An adult doesn’t dwell on that fact, like a simpering child, but instead uses it as a measure of self-worth. Knowing that life—at least the life you know on this planet in these circumstances, aside from any hope you might have of an afterlife in a heaven or hell—is finite puts pressure on you to make the best of it. You know that your years, days—perhaps even your minutes—are counting down on an invisible clock somewhere, and this thought gives you a reason to get busy and make the most of them. An adult knows that life’s ultimate meaning is not found in the words of some ancient holy man, or the benevolence of a god up in the sky or in some other dimension, or written in some sacred book. Instead, the meaning that each person finds in life is the subject of reflection and choice, of striving and sometimes sacrifice, different for me than for you, and a source of either personal satisfaction or perpetual desolation.

Animals don’t know any of this. They can’t even think of this. For them, life simply is. The striving is merely glandular, and the sacrifice is entirely circumstantial. But human beings can lift the veil, look at death, and make a sober, thoughtful choice. And that is personal power.

1. See The Original Jedi Mind Trick from May 13, 2018.

2. See In Defense of Denial from March 30, 2014.