|

|

|

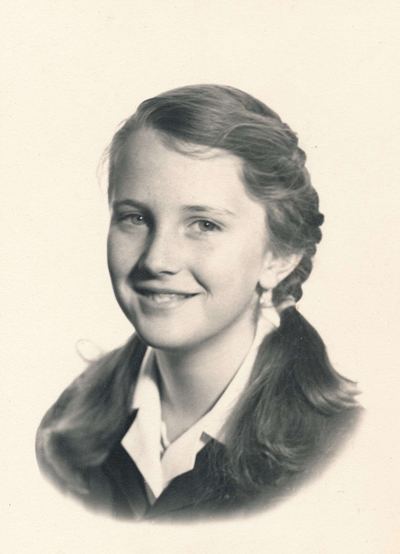

A school picture |

Note: Tomorrow, September 5, will be the fifth anniversary of my wife’s death. In her memory, here is the article, titled “The Best Life,” that I created for her celebration of life in 2017 and posted that year on our 41st wedding anniversary. I think it still reflects the best of her.

Irene Mary Moran (1940-2017) was born in San Francisco on 23rd Avenue, just north of Taraval Street, in a house her parents John and Delia Moran had owned since before the Great Depression. The neighborhood and the parish of St. Cecelia Church defined her early life and remained her spiritual home for more than sixty years.

The street she lived on brought friendships that Irene treasured throughout her life. It was also a steep street with smooth sidewalks that invited Irene and her friends to do crazy runs on their metal roller skates down toward Taraval, with only a sharp turn into the last driveway on the block—risking a fall and scraped knees or worse—as the way to stop from shooting out into busy traffic. Irene always said she got up the courage to do this after a breakfast that included a Cherry Coke.

When her beloved father died in 1948 of a heart attack, Irene’s life changed drastically. As a young man, John Moran had been a long-distance runner, had been wounded twice in World War I, and came to America from England to become a member of the U.S. Customs Service. Her mother Delia Carty had been born in Ireland, came to America in 1919, and worked for ten years as a domestic before meeting John in San Francisco in the late 1920s. John’s death put Delia, Irene, and her brother Desi in difficult circumstances. While the rest of the country was enjoying the rebound from World War II and then the economic growth of the 1950s, Delia received a modest inheritance and had to work as a school secretary. For Irene and Desi, these years were a continuation of the hardships of the Depression and the war years, and it made Irene careful about money for the rest of her life.

Irene was educated at St. Cecelia School, Mercy High School, and Lone Mountain College, where she studied history. After graduation, she worked for a while at Western Greyhound as a typist. She also had jobs during school as a sales clerk, usually at Macy’s downtown; so Irene rode the Muni streetcars on a daily basis. These work experiences—which were all that seemed to be available to a woman, even with a college education, who didn’t want to be a teacher or a nurse—convinced Irene she needed a better course. She studied library science at the University of California, Berkeley, where she took her master’s degree. This was her first time living and working in the East Bay, outside of San Francisco, and she would sometimes joke that she had moved “overseas.”

Right out of library school, Irene got a job cataloguing rare books and manuscripts at The Bancroft Library—where capitalizing “the” was a point of honor. Although she may not have realized it at the time, the Bancroft was the best place for her. It was and remains one of the most respected history libraries in the world, building on the collection of Gold Rush historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, who documented the development of California, the West, and Mexico and Central America after he arrived in San Francisco in 1852. Irene developed a great pride in the institution, made many lasting friendships in the library, and had deep respect for its Director of the time, James D. Hart.

With a permanent job and newfound freedom, Irene bought her first car—the first in her family—in 1965. It was a baby-blue Volkswagen Beetle, and she loved it. Irene was a self-taught driver and immediately took the car on a long, solo trip to northern Arizona. There she encountered her first patch of black ice, spun into a rock wall, and learned about getting her car repaired as an out-of-towner. She later took other trips in the VW with her mother to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver. She kept that car for more than ten years and then only sold it to the son of a friend.

Irene stayed at the Bancroft for 27 years, rising to the position of Head of Public Services. There she was responsible for staffing the Reading Room and preparing the quarterly exhibits of donations to its special collections for the interest of the library’s Friends organization and the many scholars who use its amazing resources. At the end of her career, as the Bancroft and similar special-purpose libraries all across the nation put the catalogues of their unique collections online, Irene learned the new skill of computer coding and access. Working at the Bancroft in a position of authority made Irene the confident, capable woman she was.

She was always ready to help visiting scholars in their particular searches. During the mid-1970s she worked with the author Elinor Richey in developing reference materials, photographs, and drawings for Elinor’s next history project, The Ultimate Victorians of the Continental Side of San Francisco Bay. The volume was being published, like Elinor’s other works, at Howell-North Books in Berkeley. Elinor kept telling Irene, who was a tall woman at five foot eleven, about this tall young editor she was working with at Howell-North. And Irene’s response would be “Yes, yes, Elinor. But about this picture …”

|

|

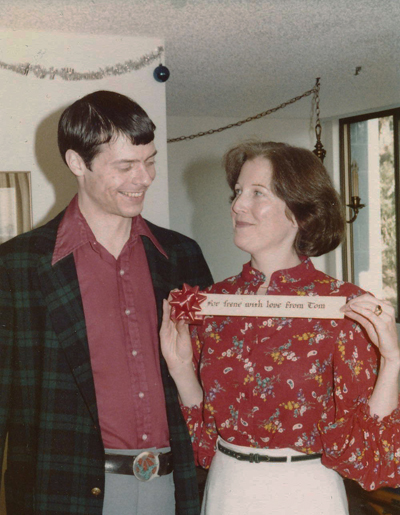

An early Christmas together |

I was the tall young editor, and Elinor would tell me about this tall librarian she was working with at the Bancroft. And my response would be “Yes, yes, Elinor. But about this sentence …” I did go into the library once to retrieve some photos, and met a tall and beautiful librarian with long blonde hair. I recognized Irene from her name badge, but the only words we exchanged was her asking me to use a pencil instead of my fountain pen in filling out an order form. In a rare book and manuscript library, ink was forbidden because a scholar taking notes might accidentally mark a precious resource. Those were the only words we spoke for more than a year. But I remembered the name Irene Moran.

We finally met formally, as in a date, in 1975 at the publishing party for Elinor’s book, which was held at the Oakland Museum of California. We liked each other enough to go to dinner afterwards. From there, we continued dating and got married a year later. Because friends of Irene’s in Berkeley had just been married by this smart, young woman judge on the circuit in Alameda and Contra Costa counties, we took our vows at the courthouse in Martinez on October 15.

In preparation for living together, we had been looking at housing in the area and focused on the Gateview condominium complex in Albany. It was an easy commute to Irene’s job on campus and had good bus and BART connections for my then-current job at the Kaiser Center in Oakland. We signed the mortgage papers while we were still single and planned to move in right after the wedding. Because we were the first occupants of that condo unit, we had the balcony enclosed and hardwood floors installed—work that needed some time to prepare. It was a beautiful location, with views of the trees on Albany Hill from one side and down the shoreline to the Bay Bridge and San Francisco on the other. The price was more than anyone in either of our families had ever paid for a complete house, and we always thought we would eventually move out to a home in the Berkeley Hills. But over the years of looking and not finding, and coming back to our condo where the sun was shining and the views were inviting, we always decided to stay. We remained at Gateview for 41 years.

A major influence in Irene’s life as a young girl was her cousin Kathleen, who was some years older. Kathleen had served in the Marine Corps and eventually managed an office in Philadelphia. She showed Irene that a strong and independent woman could be successful in the world. In 1981, in the midst of plans for moving with her fifteen-year-old son Gary to California, Kathleen died suddenly of a thrombosis. Irene decided that she wanted Gary to come out west anyway and that we would make a home for him. Gary stayed with us until he graduated from high school and joined the Air Force. Irene and I never had children of our own; so Gary and his wife Jessica and son Shane have since become our family.

Although Irene loved the Bancroft, it was always, well … work. In the mid-1980s we were watching the Alex Haley television special Roots. One of Haley’s ancestors—“Chicken George,” a slave who was also an entrepreneur raising fighting cocks—declared his intention to save his money and “buy his freedom.” That notion reverberated with Irene. She then and there decided to save her money and buy her own freedom—or be in position to take advantage of the university’s occasional retirement buyout packages. She was finally able to retire in 1991.

Irene always loved to travel. During her early years, she took a solo trip around South America including Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Machu Picchu. And she went camping in Mexico and hiking in the Rockies with friends. She also flew to Ireland several times to visit the farm where her mother grew up, and which was then in the keeping of an aunt. After she retired, Irene and I traveled to London twice, to Italy twice, to Paris, and to Amsterdam. When I was working and unable to join her, she booked travels with lady friends to Brussels, Greece, and Eastern Europe.

Her newfound free time enabled Irene to volunteer in the causes to which she felt closest. Her brother Desi had suffered a severe mental illness all his life, and that inspired Irene to join the East Bay chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, or NAMI. Over the past twenty years, she has worked as treasurer and office manager and coordinated the mailing of the chapter’s bimonthly newsletter. Early in her retirement, she also volunteered at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, joining the Monday Day Crew. There for fifteen years she and others handled the rough physical work of herding sick and injured elephant seals and California sea lions, mixing fish mash and intubating animals that could not feed themselves, and cleaning the pens. It was vigorous outdoor work, and Irene loved it.

Irene also had twenty-plus years of serving as a volunteer usher at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre. And she served two terms on the Gateview Homeowners Association Board of Directors, both during difficult times for the association.

|

|

At the Richmond Art Center |

Her mother Delia died in 2004 at the age of 102, and we always thought Irene would live as long. In her final years, Delia suffered short-term memory loss: she could recall people from her life on 23rd Avenue from fifty years in the past but couldn’t remember what she had for breakfast. This might have worried anyone else, but Delia remained a cheerful person with a gracious disposition. This gave me hope that there can be peace and acceptance under all of life’s conditions.

Irene battled depression for most of her life and alcohol in her later years. She hit “rock bottom” in the year her mother died, and then she decided to do something for herself. She joined Alcoholics Anonymous and took up their program with a will. She embraced its Zen-like demand for self-examination and self-honesty, as well as the AA tradition of service to others. She became a backbone of her home chapter, picking up and driving people to meetings and to their other appointments. Although Irene broke from the Catholic Church at a young age, she found peace in the AA concept of a higher power, or supreme spirit, and she began meditating.

Irene and I took our last trip together in the fall of 2012, to Arizona to visit the natural wonders and Native American heritage of the Southwest. This trip echoed one we had taken early in our relationship to the canyon lands of southern Utah and northern Arizona. Shortly after our trip, Irene suffered a heart attack and had a stent installed. This showed her that, in addition to her depression and alcohol, she had to work on getting exercise and eating right. She rose to this challenge as she had to the others. Irene was a brave, purposeful, dedicated woman.

Despite her efforts, her last couple of years were a time of failing health and diminished capacity. Earlier this year, she began experiencing headaches, nausea, and leg pains, which a neurologist diagnosed as an arterial inflammation, or vasculitis. On the morning after Labor Day, Irene succumbed to complications from this disease and the powerful steroid used to treat it.

Those who loved Irene knew her wonderful qualities. She lived the best of lives—strong, alert, interested, and purposeful. She was my wife, my love, my lady, and my best friend.

Irene’s favorite passages from Desiderata—

“Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself. You are a child of the universe no less than the trees and the stars; you have a right to be here.

“And whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should. Therefore be at peace with God, whatever you conceive Him to be.”