|

|

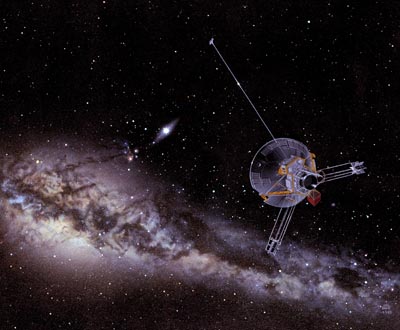

When I retired from the biotech company—now seven years ago this month—I thought of myself as boarding one of the Pioneer or Voyager space probes. I was breaking the orbit I had followed for forty years in the working world and heading out for the deep, cold place between the stars. In my mind, I wasn’t heading so much toward anything—no definite place or goal or achievement—as I was leaving behind a known existence that for me had been useful and comforting, had given my life purpose, had provided opportunities for me to excel at what I did best: explaining through written language, personal interviews, and stories the complex technical world around us.

One of the things I knew I was going to give up was a regular paycheck. But that was okay, as I had my retirement savings, Social Security, and some family resources. Another thing I was giving up was a time clock. This was less of a problem, as I have always been a regular and disciplined person. I get up at the same time in the morning—usually as the sun comes up and the birds start singing—and go to bed at a regular time at night. But now I would be able to nap in the afternoon, if I felt like it. And I would be able to spend an hour over my breakfast with the paper in the morning, instead of rushing out to join the commute to work. For someone whose life had been dominated by the clock and who measured time and tasks in five- and fifteen-minute intervals, this was pure pleasure.

The biggest thing I gave up, however, and why I thought of my retirement as heading out for unknown stars, was the duty to respond to the demands and wishes of others. For forty years, I had edited the books assigned by my publishing house; undertaken the technical assignments and communications tasks assigned by my supervisors; written the press releases, articles, and speeches that senior management wanted for the company;1 and written the novels that my agents and editors thought would sell in the marketplace. I spent my working years and my private pursuits writing with one eye looking over my shoulder to make sure I was doing what someone else thought was right and necessary.

In my fiction, I had spent twenty years and ten novels chasing the market. When you work in a genre like science fiction and publish from contract to continuing contract with a house like Baen Books, you know what the readers expect and what the publisher wants in order to satisfy them. This doesn’t mean just writing speculative fiction instead of mysteries or romances, but writing a particular kind of speculation with a certain attributes as to scientific outlook (realistic and technologically positive), political viewpoint (generally traditional, conservative, and supportive of the military), and sensitivity (humanistic, honorable, and upbeat). You accept a certain amount of literary freedom—within the parameters stated—along with the understanding that you probably will never see a million-copy bestseller or earn enough of an advance on any one book to quit your day job and write full time.2

For ten of those years apart from Baen I tried to write thrillers and literary fiction in order to attract an agent who would break me out of the genre market and enter me into the mainstream publishing world. To do this, you can’t just think of a neat idea and write a compelling query letter. You can’t even shortcut the process with the traditional outline and three sample chapters—not anymore. You can still do the outline and samples with nonfiction, where the actual writing and its result are easily projected, but then you need to have a good marketing plan to show what audience your nonfiction subject is intended to reach. But fiction is a form of vaporware—not real and solid until you cover the imaginary ground and produce the actual manuscript, although the audience is usually easier to describe. I wrote one complete thriller, Trojan Horse, and shopped it around to perhaps 1,500 different agents—you don’t even think about going “over the transom” with a publisher anymore—only to be told through a dismally small number of replies that this wasn’t a million-dollar idea. And, looking back on that book purely as a work of fiction, it wasn’t my best, either.

So part of my heading out for unknown stars was an understanding that I would no longer be writing anything based on its economic potential. I resolved instead to write what was interesting, beautiful, and meaningful to me. This is not to say I was going to become intentionally isolated and obscure. I wasn’t turning into a literary hermit in sackcloth waving a doomsday placard. I still have an eye and an ear for what a moderately well-read and sophisticated reader might want to buy and read. And I was still going to produce the best books I knew how to write. But I wasn’t going to chase any particular market. If novels about boy wizards with glasses or naïve young women in bondage to billionaires become big in the marketplace, I’m not going to be plotting how I might produce something similar to attract a publisher.3

This resolve meant I would forevermore be doing my own publishing and promotion. Early on, I learned how to code text in HTML (that is, hypertext markup language—the basis of all web design) in order to manage my own author’s website—where you are probably reading this—and produce my own ePubs to distribute as ebooks. I already knew about text editing and layout from years of working in the publishing business. But I had to learn the technical processes and make the commercial arrangements for distributing my work through reading systems like Kindle, Nook, and iBooks, and through print-on-demand book producers like CreateSpace. I had to learn how to obtain my own international standard book numbers (ISBNs) and file for copyright protection. And, because I am operating on a shoestring, I have to do my own copyediting, page and cover designs, and other technical functions that a publisher would normally provide and for which other independent authors often pay hefty professional fees.

Somedays I feel like a one-man band with a bass drum strapped to my back, cymbals between my knees, and a harmonica on a bracket between my lips. Sometimes it seems as if I am making an absurd and unmusical noise that no one would confuse with real music. And often I wonder if the faintest echo of my songs will reach any of the stars that still twinkle far off in the darkness before me.

But, for better or worse, I’m on my way!

1. Well, not always. When I became internal communications manager at the biotech company—a job I helped specify and create—I pretty much had the biweekly editorial schedule under my control, which was okay because I wrote all the articles anyway. The main goal of this job as I saw it—and senior management agreed—was to explain the business to all of our employees. In a company that made genetic analysis equipment, we employed molecular biologists, chemists, mechanical engineers, optics and laser specialists, and computer programmers—each with an understanding of their own part of the complex processes used in highly technical products. We also had an even greater number of support people in supply chain, logistics, accounting, finance, and other functions—each with perhaps only the most rudimentary notion of what our products did and how they worked. So my job was to explain new products and the science behind them so that all our employees could speak knowledgeably about the company and feel good about what we were all doing. I also looked for opportunities to interview and highlight people within the company who had singular achievements, both at work and on their own time. For a technical communicator like me, it was a dream job.

2. For those of you who still believe writing fiction is the ticket to an easy life, consider the parts that sweat equity and pure luck play in striking the market just right to bring home a bestseller. It takes me between a year and eighteen months to write a novel, from original conception to final draft—and some of my novels have been in the “noodling” stage for much longer than that. Half of this time is spent just thinking about, scoping, and outlining the story; the other half is pushing down keys in writing the notes, outline, and production draft, which is where the book lives. I can’t work eight hours a day on any of this, so the actual writing time—recorded back when we had to prepare computer logs for the IRS, so they wouldn’t think we were using these tax-deducted machines to play computer games—is 700 to 1,000 hours of straight keyboarding. Twice that, if you count the thinking and research time, plus waiting for an idea to surface from the subconscious. So a book manuscript is like a lottery ticket that costs you at least 1,000 hours of your undivided attention. But instead of odds of 50 million to one, your odds of winning big with this ticket improve to maybe only a million to one. For any given book, you would do better to take out insurance against lightning strikes and then go stand in a field during a thunderstorm.

3. And really, this was never a promising strategy. By the time a novel like Harry Potter or Fifty Shades makes enough sales to become a household word, the market is already preparing to move on. Even if you are the fastest writer in the world, able to conceive and produce a complete manuscript in three or four weeks, it would still take an agent three to six more months to consider, accept, and market it to a publisher, and the publisher would take the better part of a year to accept, edit, design, typeset, print, and market the book to their retail outlets. By that time, your pathetic wannabe novel is almost two years out of step with current market tastes and interests. No, better to write something new and original and then stand out in the field during that thunderstorm.