|

|

|

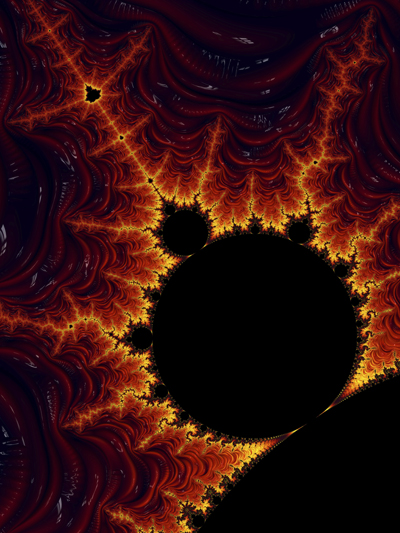

Mandelbrot fractal |

The other night I attended a concert by the San Francisco Chamber Orchestra.1 While the music was excellent, I had a “disconcerting” moment in the prelude, during the time that the audience was still filing into the auditorium and finding their seats. Rather than a curtain coming up on the whole ensemble of 36 players seated and ready to start, the stage began with empty chairs and music stands. Then, one by one, at intervals of about a minute, each player entered, took his or her seat, and began playing … something.

What each player was doing seemed like random practice: trying out a series of chords, working out a difficult passage in the evening’s music, or just tuning up the instrument. The point is, the playing was totally uncoordinated, bits and pieces rising and falling without any linkage. At one point, I turned to my companion in the audience and quipped, “I suppose they do this so it will sound better when they all start playing together.” It wasn’t quite cacophony,2 because each fragment was a nice bit of music in itself, when I could isolate it, and the overall effect lacked the crash of garbage cans, swell of police sirens, and screech of brakes. But it wasn’t exactly pleasant.

In fact, after a few minutes, I began to feel a certain discomfort, then anxiety, depression, and other negative symptoms. I actually tried to close my ears with my fingers at one point. And this reaction reminded me of something I knew long ago: that I am allergic to chaos.

This isn’t just a philosophical or political aversion. I’m not making a statement here. I just can’t stand a prolonged state of disorder, without pattern, without sense or direction. And I don’t suppose many people can—or not without suffering negative symptoms such as I did.

You would think that I then must hate nature, which is itself fairly chaotic. But within the movements and displays of the natural world, there is generally a pattern that can be discerned in one pays attention over time. The wind in the trees, the falling of leaves or blowing of snow, the ripples in sand dunes … all are patterned. Each trunk and limb in the forest can bend only so far, and then it must bend back, so that the swaying of the trees has a regular span and rhythm. Each wave on the beach is followed by another in a regular succession. Birds migrate with the seasons. Bees swarm and then find their hive. Night follows day follows night. The Moon progresses in its phases, and shooting stars come in orderly streaks from a focal point in the sky. Even the eruptions of volcanos and their lava flows tend to follow a pattern over time.

The trouble is that, given a patternless chaos, my brain automatically tries to make order and sense of it. I try to find a pattern, at some level, large or small, like the inner workings and infinite regression of a Mandelbrot fractal. I do this even when I know there is no pattern and can be no pattern. That night at the concert I knew and understood that all of this musical nonsense and not-quite-noise intentionally held no pattern. And yet my brain tried to make music out of it.

This may explain why I am made nervous in crowds—aside from the obvious possibility of a mob breaking out and carrying me off screaming—or in packed spaces like restaurants and, ahem, theaters before a show starts. There can be found patternless voices, snatches of conversation, and random bumps and thuds. There chaos hangs in the air, mutters and teases at my ear, and sends my brain into fits trying to isolate snippets and make sense of the loose and vacant chatter.

This may also explain why I am made nervous by the laser light shows that generally accompany rock concerts as well as by the jumble of flashes and bangs that generally form the “blowoff” ending to a fireworks display. One, two, or three rockets exploding together and mixing their starbursts and showers, or the calmly rotating reflections of a disco ball … these are agreeably patterned. The sporadic lightning and booming of twenty rockets going off at once, or the artfully programmed confusion of light beams swirling, swooping, and dancing on smoke … that’s nervous-making.

While I am a dedicated wargamer and love the simulated strategic problems of a miniatures battle or board game, I would hate being in a real war. Even when an opposing gamer makes a surprise move—and it’s interesting how, at the height of battle, the reactions of other players are generally not all that surprising—the situation is still somewhat controlled. We have rules in each gaming system about how far rifles and artillery can fire, how far a unit of troops or vehicles may advance in any one turn, and what sequence of play each side must follow. The progression is orderly if not exactly predictable. But in the real thing—and I know this from having played paintball, which is a lifelike tactical engagement, with all its crawling around in the dirt trying to find cover, except that plastic shells filled with water-soluble paint replace actual lead bullets—fire comes in from all sides, intermittently, without any sequence or pattern. You lift your head to look one way and—splat! A sniper who’s been watching your position has just torn open your skull. Surprise, you’re dead! My brain hates that! There is no way to predict disaster and guard against it.

But all of this is not to say that I hate uncertainty. That is a different thing. I am quite comfortable with unanswered questions, like the nature of God, the origins of life, the conspiracy behind the Kennedy assassination, and other situations that may or may not be ultimately knowable but right now are open to question and speculation. In fact, I am more comfortable with a complex uncertainty (e.g., how do those mutant geniuses manage to solve Rubik’s Cube with just a few twists?) than I ever would be with a simple but possibly wrong or inadequate answer (e.g., God said it, the Bible records it, I believe it, that settles it). I can tease out and isolate the uncertainties and missing pieces of an argument or line of reasoning. I don’t have to squash or answer them. My brain is satisfied with just knowing where the potholes are.

But in a flood of random sounds or the flash of random lights—think of the display of little twinkling bulbs that 1950s television shows used in a display panel to suggest a computer at work—I am bothered because the signal becomes indistinguishable from the noise. You cannot isolate and examine uncertainty when an overall pattern does not even give you a framework to begin analyzing.

So, while the chamber orchestra may have found an interesting and dynamic way of bringing the concert experience into focus, they also point to a certain weakness. Thank goodness, this group plays mostly classical works that celebrate order, transition, and resolution, rather than some of the more modern composers—here I’m looking at you, Shostakovich!3—whose works are sometimes indistinguishable from disorganized noise itself.

1. The program started with the Faust Overture by Emilie Mayer, a 19th-century German composer of whom I had not previously been aware. That was followed by the more familiar Fifth Symphony of Beethoven. The treat of the evening was hearing Music Director Ben Simon and various sections of the orchestra “disassemble” the Fifth to show how the composer used key changes, variations, and repetition to build this musical masterpiece.

2. If you break this word down linguistically, kak in Greek means “bad,” and phonia means “sound.” So this is—now from Latin roots—dissonance or “bad sound.” Given how kak and its variations are usually rendered in many languages, it could also be “shit sound.”

3. Although I am partial to his Symphony No. 10, particularly the rousing and martial Second Movement.